|

The History of the Zeppelin

Part Three: 1929 to 1940

|

In August 1929, LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin departed on a grand adventure: a complete circumnavigation of the globe. The growing popularity of the "giant of the air" made it easy for Dr. Eckener to find sponsors. One of these was American press tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who requested the tour officially start in Lakehurst.

|

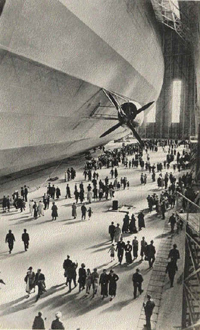

Passengers board Graf Zeppelin

|

From there, Graf Zeppelin flew to Friedrichshafen first, continued across Russian Siberia to Tokyo, then across the northern Pacific to San Francisco and Los Angeles, and across America back to Lakehurst. Finally, the Graf recrossed the Atlantic to her home port of Friedrichshafen. The voyage was a triumph: she completed a circumnavigation of the globe in only 21 days, 5 hours, 31 minutes, setting a record. Including the initial and final trips from Friedrichshafen to Lakehurst and back, the Graf travelled 49,618 km.

|

|

In the following year, Graf Zeppelin undertook a number of trips around Europe. Following a successful tour to South America in May of 1930, Zeppelin decided to open the first regular transatlantic airship line. Despite the beginning of the Great Depression and growing competition by fixed-wing aircraft, the Graf would transport an increasing number of passengers and mail across the ocean every year until 1936.

|

Passenger Clara Adams poses in front of Graf Zeppelin

|

Graf Zeppelin pursued another spectacular adventure in July of 1931 with a research trip to the Arctic. This had already been a dream of Ferdinand von Zeppelin twenty years earlier. Only now was it possible.

|

|

Dr. Eckener intended to supplement the successful airship with another, similar Zeppelin, projected as LZ-128. However the deadly accident of the British passenger airship R101 in 1931 led the Zeppelin company to reconsider the safety of hydrogen-filled vessels, and the design was abandoned in favour of a new project. The newly-planned LZ-129 would advance Zeppelin technology considerably, and was intended to be filled with helium, an inert gas.

|

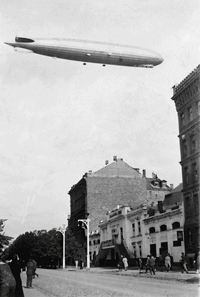

Graf Zeppelin over Riga, 1930

|

|

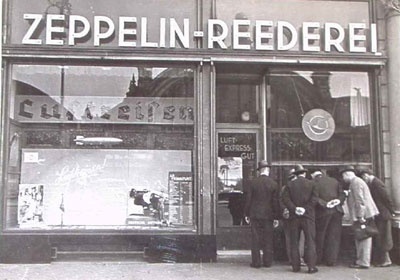

After 1933, the establishment of the Nazi dictatorship in Germany began to overshadow the Zeppelin business. The Nazis were not interested in Eckener's ideals of peacefully connecting people. On the other hand, they were eager to exploit the popularity of the airships for propaganda. Dr. Eckener refused to cooperate, so Hermann Göring, the Nazi Air minister, formed a new airline in 1935, Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR), which took over operation of airship flights. Zeppelins would now prominently display the Nazi swastika.

|

Queue at the DZR Ticket Office, 1936

|

On 4 March 1936, LZ-129 Hindenburg, named after the former President of Germany Paul von Hindenburg, made her first flight. However, in the new political situation, Eckener was unable to obtain the helium to inflate it due to a military embargo; only the United States possessed the rare gas in usable quantities. So, in what ultimately proved to be a fatal decision, the Nazis, over Eckener's objections, ordered Hindenburg filled with flammable hydrogen. Apart from numerous propaganda missions, LZ-129 began to serve the transatlantic lines together with Graf Zeppelin.

|

South America in Three Days!

|

On 6 May 1937, during landing operations in Lakehurst following a transatlantic flight, the tail of LZ-129 Hindenburg caught fire. Within seconds the zeppelin burst into flame, killing 35 of the 97 people on board and one member of the ground crew. The actual cause of the Lakehurst disaster remained undiscovered. Some modern researchers have hypothesized that a new coating material on the skin of the dirigible may have played a key role in the accident.

|

Whatever caused the disaster, it led directly to the end of airship transportation. Public faith in the security of dirigibles was shattered, and transporting passengers in hydrogen-filled vessels became totally unacceptable.

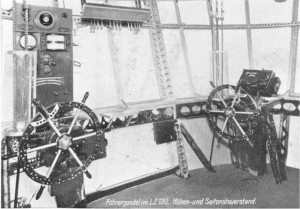

LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin was retired one month after the disaster and turned into a museum. Dr. Eckener kept trying to obtain helium gas for the Hindenburg's sister ship, LZ-130 Graf Zeppelin II, but in vain. The new flagship was completed in 1938 and, inflated with hydrogen, made some test flights, but she never transported any passengers.

| Another project, LZ-131, was designed to be even larger than Hindenburg, but her construction never progressed beyond the production of a few skeleton rings. Dr. Eckener, an unapologetic anti-Nazi, was exiled to Friedrichshafen. |

The Empty Cockpit of Graf Zeppelin II

|

After the German invasion of Poland, the Luftwaffe ordered LZ-127 and LZ-130 moved to a large Zeppelin hangar in Frankfurt, where the skeleton of LZ-131 was also located. In March 1940, Göring ordered the destruction of the remaining vessels and the aluminum parts were fed into the German war industry. In May of that year a fire broke out in the Zeppelin facility, which destroyed most of the remaining parts.

The dreams of Graf von Zeppelin and Dr. Eckener seemed to have ended forever.

|

Copyright ©2007 Puget Sound Airship Society

|

|

|

|